New writers should steal – 7 lessons from a comedy legend

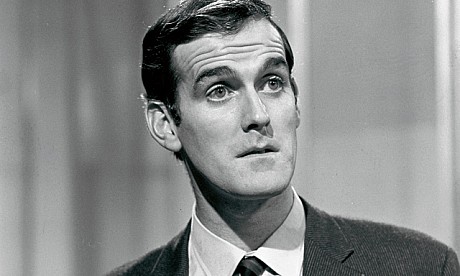

I have just finished reading John Cleese’s autobiography “So, Anyway…”

As an aspiring comedy writer, it is one of the most inspiring books I have ever read.

Cleese succeeded because he followed his ‘passion’ for comedy, and his story contains some great advice for comedy writers and performers.

There are 7 lessons that remain fundamental to modern day comedy creators.

1. Steal

That’s right, steal. John Cleese talks about how difficult it is to become really good at writing comedy. He says:

“If I may give a word of advice to any young writer who, despite the odds, wants to take a shot at being funny, it is this. Steal. Steal an idea that you know is good, and try to reproduce it in a setting that you know and understand. It will become sufficiently different from the original because you are writing it, and by basing it on something good, you will be learning some of the rules of good writing as you go along.”

I’m not a legal expert but I think it’s clear he isn’t talking about infringing copyright. The point I take away is this. Take a successful comedy you really enjoy, study the idea, structure and set up, and practise writing using that format based on your own experiences.

Ultimately as comedy writers we should and will develop our own unique style. But the message here is to be aware of what has worked before and why, to understand what it takes to write a strong comedy script and try applying the techniques to your own work.

2. Generating ideas

Cleese talks about how he and writing partner Graham Chapman came up with ideas for Monty Python. They started by using a Thesaurus.

As usual I picked up Roget’s Thesaurus and started reading words out at random.

‘Buttercup. Filter. Catastrophe. Glee. Plummet.’

‘Ah,’ Said Gra. ‘I like plummet.’

A couple of minutes passed.

‘A sheep would plummet, wouldn’t it?’ one of us said.

‘If it tried to fly, you mean?’ said the other.

‘But why would it want to fly?’

‘To escape?’

A couple of months later the ‘Flying Sheep’ became the first Monty Python skit to be recorded.

This initially struck me as an unusual way to generate comedy ideas. Generally the best ideas come from our own personal experiences (which probably rules out a sheep flying for most people). But it is a really interesting approach, and shows that actually the initial idea is just providing some inspiration, and that the creative development of the idea and characters is what makes it something really funny.

Cleese talks about the difference between realism and believability. You can have a very abstract idea that is in no way “realistic”, but the traits of your characters and how they react to their situation needs to remain consistent and “believable” throughout your sketch or sitcom.

This idea is also developed in one of the brilliant Tony Zhou “Every Frame a Painting” videos about Chuck Jones – Evolution of an Artist, where Tony demonstrates that you can have fantastical characters but they must follow a set of rules.

So maybe a flying sheep isn’t that absurd a place to start after all, as long as the sheep’s response to flying is the same as it’s response to other equally unusual and scary situations it finds itself in.

3. Writing with a partner and in a sketch team

We have talked before on the blog about the benefits of working with others, having a writing partner and being part of a team that can bounce ideas of one another making the creative experience more enjoyable. But to hear it from John Cleese and see how it lead to such great success is very inspiring.

Cleese worked most of his comedy career with writing partner Graham Chapman. They first met in the Cambridge Footlights, and wrote together for many TV shows, films, and of course Monty Python. Cleese says:

When you begin to write comedy, the biggest worry is simply: is this funny? Writing with a partner ensures you get priceless feedback and Graham and I worked together well: we found each other funny, and when we did laugh we really laughed.

Here is his experience of being part of a comedy sketch team for the first time at Cambridge:

What I liked most was being part of a team, and working with a common aim in co-operative spirit. The in-jokes, the friendly teasing and mutual helpfulness created a confidence, a feeling of being emotionally supported, that was the most motivating force that I had ever experienced.

4. The benefits of cutting out material

I know from personal experience how hard it is for new writers to get used to cutting their work, being able to detach yourself from the words that you created and accept that losing it may be for the best.

Here is what John Cleese says about the Cambridge Footlights show once they had started taking it on tour and cutting the material:

Our show had definitely got better since its Cambridge incarnation. It was now only sixty minutes long, teaching us that if you have an average show, and you can dump half of it, it doesn’t get a bit better – it gets a lot better. In fact, there seems to be a basic, rather brutal rule of comedy: ‘The shorter the funnier.’ I began to discover that whenever you cut a speech, a sentence, a phrase or even a couple of words, it makes a greater difference than you would ever expect.

Cleese backs this up by saying how hard it is to write a comedy film, because you cannot keep it consistently funny for more than 30 minutes or so, which means you need to keep the audience engaged through other aspects of the story. For those of us who have not yet been fortunate enough to have a comedy film commissioned, the message here is keep your early writing short, and get used to editing and cutting your work to make it as consistently funny as possible.

5. Productivity and writers block

Everyone who has tried any form of creative writing knows how this feels. Writer’s Block. Seemingly wasting limited time when inspiration just won’t come. It is reassuring to hear John Cleese talk so openly about this:

I would start in the morning with a blank sheet of paper, and I might well finish the day with a blank sheet of paper (and an overflowing waste-paper basket). There are not many jobs where you can produce absolutely nothing in the course of 8 hours, and the uncertainty that produces is very scary. You never hear of accountant’s block or bricklayer’s block; but when you try to do something creative there can be no guarantee anything will happen.

He also talks about how he became more relaxed when writer’s block set it, with the help of Peter Titheradge, former BBC producer and West End revue writer:

[Peter] got me to understand that, if you kept at it, material would always emerge: a bad day would be followed by a decent one, and somehow an acceptable average would be forthcoming. I took a leap of faith, and my experience started to confirm this mysterious principle.

The lesson here it to accept that those days happen even to the best and that slow days are a prelude to good ones. Writer’s block itself is not a problem, but panicking about it is. Which brings me to point 6.

6. The creative principle of anxiety

How we perform, how we are perceived, the impression we give is heavily dependent on our mental state. If we feel confident, we generally portray confidence. And vice versa. A good performance or action leads to a positive feeling.

John Cleese relates these ideas very well to writing comedy:

Writing and performing … taught me an important creative principle: the more anxious you feel, the less creative you are. Your mind ceases to play and be expansive. Fear causes your thinking to contract, to play safe, and this forces you into stereotypical thinking. And in comedy you must have innovation, because an old joke isn’t funny. I therefore came up with Cleese’s Two Rules of Comedy Writing:

First Rule: Get your panic in early. Fear gives you energy, so make sure you have plenty of time to use that energy.

Second Rule: Your thoughts follow your mood. Anxiety produces anxious thoughts; sadness begets sad thoughts; anger, angry thoughts; so aim to be in a relaxed, playful mood when you try to be funny.

This second “rule” is a great tip and one that definitely works for me. It also relates to point 5 about writer’s block. Don’t feel stressed when the ideas won’t flow because that will only encourage anxiety and create a vicious circle. Creating a positive mindset is a far more productive way to bring the best out of your comedy writing.

7. Pursuing activities for love, not money

I wanted to finish on this one because it is both humorous and the real overriding message from the autobiography. Cleese makes this point:

British journalists tend to believe that people who become good at something do so because they seek fame and fortune. This is because these are the sole motives of people who become British journalists. But some people, operating at higher levels of mental health, pursue activities because they actually love them. Thus I was drawn into comedy in a way I can’t quite explain but can definitely acknowledge.

Throughout the autobiography it is clear that John Cleese pursued comedy because he loved doing it, never with a direct long term plan for turning it into a career. The success came as a result of throwing himself into something he enjoyed doing.

This is a principle we can all apply, even if we are not 6 foot 4 with a remarkable gait and a bank of facial expressions to perfectly portray the rising frustration of a hotel manager or dead parrot owner.

The world of entertainment is very different now than it was in the 60s, but it feels like comedy is as relevant as it ever has been before. John Cleese and the Monty Python troupe changed the face of British comedy at the time. There are lessons we can take on to move it forward again today.

[membership level=”0″]

To make sure you stay up to date with the latest opportunities and insights in the world of comedy, join thousands of creators and fans receiving our free weekly newsletter plus when you subscribe you’ll get our e-book – Getting started and making an impact in comedy:

[/membership]

As you may have gathered I can’t recommend this book highly enough. You can read it yourself through the link below: