How to write a comedy sketch

We posed 2 sketch writing questions to comedy coach Chris Head.

- How do you generate ideas for a sketch?

- How do you end a sketch?

The answers are like a detailed “how to” for comedy sketch writing. Hugely insightful and a must read for anyone interested in the art. Here they are:

1. Any tips for finding ideas or premises for sketches? Not just topical sketches like Newsjack, but sketches in general?

Unless you happen to conveniently already have a funny idea, the best way to generate an idea for a sketch is to start with a real situation from life and work step-by-step towards a sketch idea. Below is a process to produce sketch ideas from everyday life situations; e.g, in a shop, at the doctor’s, on a date etc… Follow this 3 or 4 step process to generate a sketch. You can stop at step 3 if you have a viable idea that tickles you or you can proceed to step 4 to try and heighten the idea. And of course if you don’t get an idea that tickles you, then return to the start and work through it again.

Step 1

Choose a situation from life. Below are a few I’d suggest. Do add some or make your own list. The main thing is not to try and think of a funny subject area. Play it straight at this stage. Note, you can modify this process for parody sketches. Simply start with a list of programmes or movies etc instead of life situations. And to produce topical or satirical sketches start with a list of news stories.

Focusing on everyday life situations:

Work

Home life

Friends/ social life

Family

Institutions

Sport

Shopping

Services

Travel

Teaching & training

Pick one and then reflect on situations in this context that you have either:

– experienced directly

– or witnessed first hand

– or been told about second hand

You are looking for situations that were in some way absurd.

If you were in the situation yourself:

– You can either be the one struggling with the absurdity

– Or the cause of the absurdity (and the other party is the one trying to deal with it)

Or you may have witnessed it or heard about it. If find yourself having trouble thinking of something absurd, you can take a step further back and ask yourself what annoyed you. Once you have found something annoying then ask yourself what is absurd about it. Being annoyed (or even angry) can be a good starting point but to get it to somewhere funny you need to identify the absurdity.

Here’s a simple example of an absurdity. This morning a delivery man appeared at my doorstep (home life) and was fiddling around with papers and asking me to sign for something but he hadn’t told me what it was and it was not in sight. In this case it was an oversight but before he cleared it up there is a clear absurdity right there.

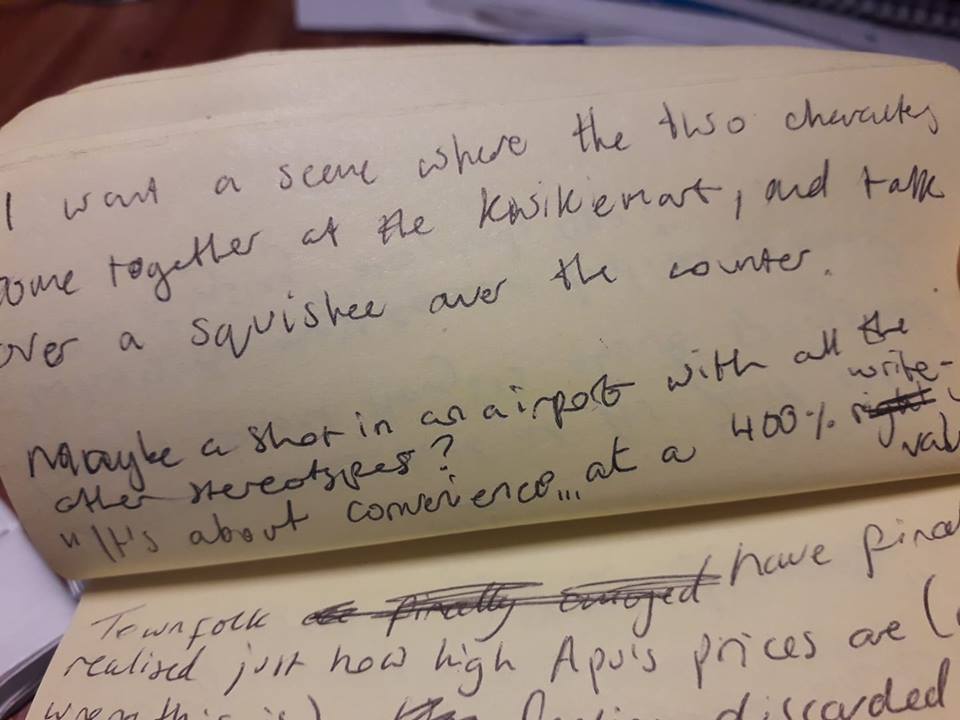

Keep a notebook of these kinds of observations – they can turn into sketches.

An example that became a classic sketch is when Michael Palin returned a car to the garage he’d bought it from because there were problems with it. The absurdity was the mechanic denying there was a problem with the vehicle when blatantly there was. He told John Cleese about this situation in conversation and Cleese felt there was a sketch in it.

Step 2: Set up the dynamic

Having identified a situation with an absurdity you then need to set up the sketch dynamic. You will need two points-of-view (POV) in the sketch.

– The absurd point-of-view (the protagonist)

– The normal everyday point-of-view (the foil)

The one with the absurd POV is the comic protagonist: they are stopping the situation from proceeding normally, reasonably or logically. The one with the normal POV is the foil as their reactions are needed to heighten the absurdity and create the comedy.

The simplest way is to make it a two-hander but you can have any number of characters as long as there are two points of view. For example, a three-hander with two points-of-view could be a married couple with the normal POV and a marriage guidance counsellor with the absurd POV. Or on a bigger scale twenty-two footballers with a normal POV and one referee with an absurd POV.

In the case of the faulty car:

– Normal POV: customer – the foil

– Absurd POV: mechanic – the protagonist

Now you need to ask yourself why the protagonist holds that absurd perspective. Normally it’s:

– They just do. It’s the McGuffin of the sketch. You don’t need to explain it or justify it.

But sometimes there is added value in giving them a motive. Here there is a strong sense that the mechanic is trying to fob the customer off to avoid expense and work. The alternative would be he is simply mad and genuinely doesn’t see any problems with the car.

And finally, boil down the situation into a game:

The game of the car sketch for the protagonist (the mechanic) is to get the customer to accept there is no problem with the car and to go away.

The game for the foil is to make the mechanic accept that there is a problem.

They stick to their POVs and play out this game. The game is them trying to solve their problems. The customer’s problem is his car is broken, the mechanic’s problem is he doesn’t want to spend time and money dealing with this car. OR if the mechanic is simply mad, from his POV his problem is trying to make the customer see there is no problem with the car. (If you follow that fine distinction).

Step 3: Heighten the absurdity

Now you have your situation, absurdity and characters you can now find the funniness by asking yourself:

What would make the situation more absurd?

Or from the character’s points-of-view:

What would make the problem worse for your foil? Or put another way, how could the protagonist’s attempts to solve their problem and get what they want be more absurd?

Here you take the existing situation and heighten the absurdity. In the case of the delivery man not revealing what he is delivering, in reality he quite soon realised his oversight and told me. In the sketch version you can heighten the absurdity by having him simply refusing to reveal what it is (is it a letter, a parcel, a fridge, a three piece suite…) until he has a signature. The recipient would be reluctant to sign and would want to find out what the thing is. The deliver man would refuse until he had a signature. And so on. Going round and round this argument with both characters sticking to the game and trying to solve their problem is what makes a sketch.

In the case of Michael Palin’s car situation, Cleese and Chapman wrote it up into a sketch for the 60s sketch show How to Irritate People (Chapman and Palin performed the sketch). The absurdity was heightened by the foil’s problems with the car being dangerous and blatant – eg the gear stick comes off, the doors fall off etc. The protagonist’s attempts to solve their problem, to get out of dealing with the car, are even more unreasonable and ridiculous than in real life.

Notice that YOU ONLY NEED ONE IDEA FOR A SKETCH! New writers often try too hard. They think: it can’t be enough, just having this man trying to get his car fixed! I have to introduce more funny ideas. YOU DON’T! Just develop and heighten this one idea, which is what Cleese and Chapman do.

This is enough to make a sketch. You can stop here is you have an idea that is tickling you. If you want to try and more out of it, move on to the next step.

Step 4. Change the given circumstances

If you want to try and get more out of the sketch you can try changing the given circumstances of the original situation. They key thing is to maintain the game and the dynamic. For example:

Change WHO: Try changing the protagonist or the foil to different characters. Eg: make one or both children or babies or dogs or celebrities or ghosts etc..

Change WHERE: Move the characters and situation to a different context.

Change WHEN: Move it to the past or the future.

For our delivery sketch, I think there could be mileage in changing where it takes place – e.g. it’s in the maternity ward of a hospital and the midwife won’t reveal the sex of the baby being delivered. This is upping the ante – it can often be an idea to look at how you can up the ante of the scenario. Or you could change when and put it in a historical period but keep everything we recognise about modern day deliveries.

In the case of the faulty car sketch, when Cleese and Chapman revisited the idea for Monty Python, Chapman suggested instead of someone taking a car back to a garage it could be someone taking a parrot back to a pet shop. Then the question is: what’s wrong with it? The answer: it’s dead, that’s what’s wrong with it.

They also introduced an additional game for the foil, the customer. He has to find as many different ways of saying the parrot is dead as possible. Notice that this is not simply because it’s funny; he is trying to solve his problem of getting the pet shop owner to recognise the parrot is dead.

You can make all sorts of changes. For example:

Change HOW: This could be how characters are behaving, speaking, moving.

Change WHAT: Change what the central object or subject is.

Change WHY: Change the character’s reasons or motivations for their actions.

All of these kinds of changes have potential comic mileage provided the starting point was a real, recognisable situation. If you start with an unreal funny idea it can drift too far away from anything recognisable and not be grounded in anything the audience recognise.

Then write the sketch!

The last thing to do is write the dialogue. An issue writers can have with sketches is that they launch into dialogue before everything is thought through. Starting to write dialogue with unclear POVs, an ill-defined dynamic between the characters, little sense of the game of the sketch or what problems the characters are trying to solve is a recipe for producing an unclear and ultimately unfunny sketch. Audiences do not laugh if they are struggling to make sense of things like: who are these people, where are they, what do they want, what’s stopping them from getting it…

And finally, the structure to write your sketch in is:

Set-up: Establish the who, where, what etc. The given circumstances. Do this economically. (There can be laughs here but the game, the central comic idea, is not yet revealed).

Reveal: Having set it all up you now reveal the game of the scene.

Escalation: The characters play the game; they try and solve their problems.

Pay-off: A surprise conclusion or twist.

And how do you generate a pay-off? See my answer to the next question!

2. Can you give some tips for writing effective sketch endings / resolutions?

Yes, endings can be the biggest problem with sketches. John Cleese bemoaned that he and Graham Chapman would write a sketch in a morning, then spend another week trying to end it. Python themselves of course abolished the punchline with meta endings and stream-of-consciousness flowing from one thing to the next. Aside from doing that, here are three initial very common and effective endings. I will explore in a follow up response…

A VERY common ending. The straight character suddenly buys into the worldview, or takes on the behaviour, of the funny one.

eg: If in the sketch a man has gone into a library, asking reasonable questions but shouting his head off, then the reversal pay-off has the hitherto straight librarian shouting their head off.

This is either done inexplicably or in a calculated way. See Fry & Laurie’s policeman/ name sketch for a calculated version.

Another classic. It looks for a moment like the torment is over for the persecuted character, or the problem is solved, but in fact it isn’t. False dawns can also work mid-sketch – they can serve as a breather in the escalation.

e.g: A waiter has been getting two diners more and more annoyed by bringing the wrong dishes. Finally it seems he has understood and is now going to bring the right dish. The couple relax, but he gets it wrong again (but in a new or more extreme way).

See the ending of Rowan Atkinson’s Fatal Beatings.

A new character comes in and enters the situation.

It may be that we know what’s going to happen but they don’t. (Dramatic irony.)

Or they can be a way of the sketch starting again, the whole thing going full-circle (see below).

Or they can changes our perspective on the situation or the existing characters’ relationship to one another. (A way to bring out an ‘extra killer fact’). e.g: A patient has been struggling with a very strange doctor in a hospital. Then a psychiatric doctor comes in and takes the original “doctor” back to the mental ward.

See Armstrong & Miller’s man who doesn’t know what his job is.

Here are some further ending ideas:

Extra killer fact

A revelation that casts everything that came before in a new light. Be wary of these though. Make sure the sketch is funny in its own right prior to the pay-off. (Or make it a quickie).

e.g: We don’t discover until the end that the two women chatting about babies are actually chatting about their husbands.

Variation

The punchline provides a variation on the central joke.

e.g: If the sketch was about the mayor complaining that squirrels were being employed to drive buses, the variation could be underground trains being driven by lemurs. (Bit surreal but you get the idea!)

Meta ending

The artifice of the situation is acknowledged, or the illusion is broken in some way, or the conventions of the performance situation are broken or exposed.

E.g: “I’ve forgotten the punchline for this sketch so let’s end it here.”

End on a strong laugh line

The sketch just ends on a good line. It doesn’t twist again or do something unexpected, it just stops on a particularly funny line.

It was all a trick…

The situation is revealed to have been some sort of practical joke or trick. This can be used as a false dawn too.

Victory

One of the characters wins the dispute or gets their own way. Needs to be done in an unexpected way. Can be effective if the victim of the scene suddenly turns the tables.

Violence

One character hits, attacks, shoots, kills etc the other. Fry & Laurie did lots of these and Python did a few too.

Natural end

The scenes just end naturally, on a dramatically right note.

Full-circle

The sketch finishes as it begun with no progress having been made.

Mix into the next item

As I said at the outset, the Python’s (and Spike Milligan’s) solution to the problem of ending sketches. They don’t end, they just flow in to the next one.

So there you have it comedy creators. If you found this helpful and want more comedy opportunities, tips and tricks, our weekly newsletter inspires 10,000+ comedy creators every Monday. Receive it for free here

And hot off the press! Chris Head has just released his latest book Creating Comedy Narratives for Stage and Screen.

Three thirty-minute plays come together to create a unique evening of theatre that explores the last century of women’s rights. Stevie’s piece ‘The Flour Girls’ is a surreal comedy that looks at the night in 1970 when British feminists flour-bombed the Miss World contest – from the perspective of two bags of flour…

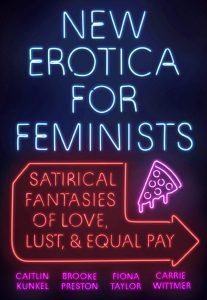

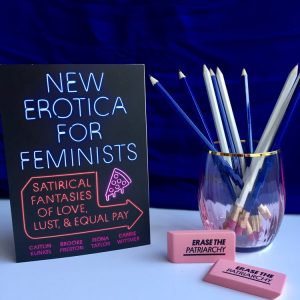

Three thirty-minute plays come together to create a unique evening of theatre that explores the last century of women’s rights. Stevie’s piece ‘The Flour Girls’ is a surreal comedy that looks at the night in 1970 when British feminists flour-bombed the Miss World contest – from the perspective of two bags of flour… Sounds like the dream right? Brooke, Caitlin, Carrie and Fiona make up Belladonna Comedy. They run their own popular satire website and are shortly releasing their first book “New Erotica for Feminists”.

Sounds like the dream right? Brooke, Caitlin, Carrie and Fiona make up Belladonna Comedy. They run their own popular satire website and are shortly releasing their first book “New Erotica for Feminists”. We set to work immediately, setting up the site’s infrastructure and branding (by illustrator extraordinaire Marlowe Dobbe:

We set to work immediately, setting up the site’s infrastructure and branding (by illustrator extraordinaire Marlowe Dobbe:

In the UK: Waterstones, Amazon, Apple Books, Sceptre’s website, independent booksellers and (in theory at least) everywhere books are sold. Ask your local bookseller to carry it!

In the UK: Waterstones, Amazon, Apple Books, Sceptre’s website, independent booksellers and (in theory at least) everywhere books are sold. Ask your local bookseller to carry it!

Or buy your own copy of the book here:

Or buy your own copy of the book here: